Subnautica and Sound

June 24, 2020

Gothic writer Ann Radcliffe had very different definitions when asked the difference between horror and terror. Terror, in basic terms, relates to the psychological effects of suspense, and the threat of danger, while horror is the actual act of being scared, or shown something gross. Because both terms have different applications, they are both used in different contexts, especially in video games. Many horror games are just that — they employ jumpscares, timing, and ambiance to scare the pants off of their players. Horror is primal — it plays on our instincts to react to threats that we gained from our ancient ancestors. While it’s much more “engaging” in this space, it’s often quite cheap — playing through Resident Evil a second time doesn’t have the same effect because we know what’s coming.

Terror, on the other hand, is much more than its face value. It’s claimed that the idea of terror is unique to humans because we have the capacity to imagine, which when put to the test (say, on an alien planet with expansive environments full of things that *might* kill you) can run rampant with bad thoughts and premonitions on what might happen next.

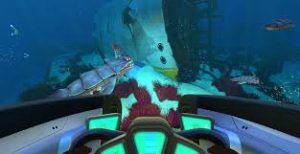

This is where open-world explorer Subnautica capitalizes on its environment — by using the potential for danger much more than it uses jumpscares, NPC attacks, and other actually dangerous elements. There are a couple of methods by which publisher Unknown Worlds Entertainment goes about employing this sense of terror. A lot of this comes from the game’s design. Subnautica’s designed terror is a perfect attribution to Radcliffe’s definition — it enlightens the senses of the player by giving them just enough information to know that they should be cautious (scared), but not enough to claim mastery or know how the various predators function. I could go on for pages on the way the design of the game lends itself to the horror genre, but what I’m here to talk about is how *Subnautica* uses sound to employ its terror and keep the player huddled around their lifepod as long as they can.

The screeching roars of the game’s leviathans — essentially mini-bosses — are absolutely horrifying the first time they’re heard, but Subnautica makes things interesting by employing them at strategic times. I noticed in my playthroughs that, because most of the map is available from the start of the game, the player is liable to explore at their own whim. The Reaper Leviathan is by far the scariest predator in the game, mostly because of its piercing, guttural roar that can be heard from up to five kilometers away — about a quarter of the map’s distance at any given point. It immediately puts the player on their toes, especially when they learn that the Reaper only roars when it can see them — something I didn’t even know until I researched this article. Because the Reaper’s mechanics tell it to encroach, surround, and then attack, hearing the roar could mean the Reaper is a mile away, or right behind you. The game also capitalizes on its three-dimensional space for this. There are no walls in *Subnautica*, besides caves and rocks, conveniently away from where the Reapers like to reside. A lot of the game’s loot — primarily found in crash sites and wrecks — are out in the open, where the Reapers are not only present but plentiful. According to subnauticamap.io, there are 22 potential spawn locations on the map, all concentrated in three essential areas. No getting around these guys.

Cues are also a significant factor in using sound to create the atmosphere in Subnautica. Resident Evil 4, a quintessential game in the horror genre, made use of a limited perspective, and audio cues. Enter a room and can’t see all of it? You’re probably getting jump scared. Subnautica uses a similar effect but is able to use a wide range of space because of the nature of the game. When you’re on land, you only have to worry about what’s around or above you. However, when you’re in space, or underwater, in this case, you have to worry about the entire area around you. This makes it much more terrifying to check behind you in open fields, around corners, or in caves. Every biome, structure, or rock face is made terrifying by this ambient structure, making the known safe areas a haven for the weary traveler.

Like other games in the genre, Subnautica capitalizes on the absence of noise as much as it relies on it. It does this by taking advantage of the space — get it? — that the player finds themselves in at the start of the game. Planet 4546B, as you can see, doesn’t even get a name in Subnautica. It’s completely unknown, and suddenly you’re the only survivor on a vast, seemingly barren planet. Because nearly the entirety of the game is spent underwater, it can get awfully quiet. The game’s accompanying AI, found on the PDA, even pokes fun at the player for the attachment they’ll form with the lone human voice:

“After weeks without human contact, it is normal to experience psychological discomfort. Research indicates symptoms may be partly alleviated by adopting a pet or anthropomorphizing an inanimate object.”

See that? The game is very aware that the main protagonist hasn’t heard a human voice in a long time, and if the player has racked up several hours in a play session, maybe they haven’t either.

There are tons of environmental ways that Subnautica chooses to mess with the player, and by taking advantage of the sounds provided by the environment, or lack thereof, it can provide an interesting case study in non-scary horror games.