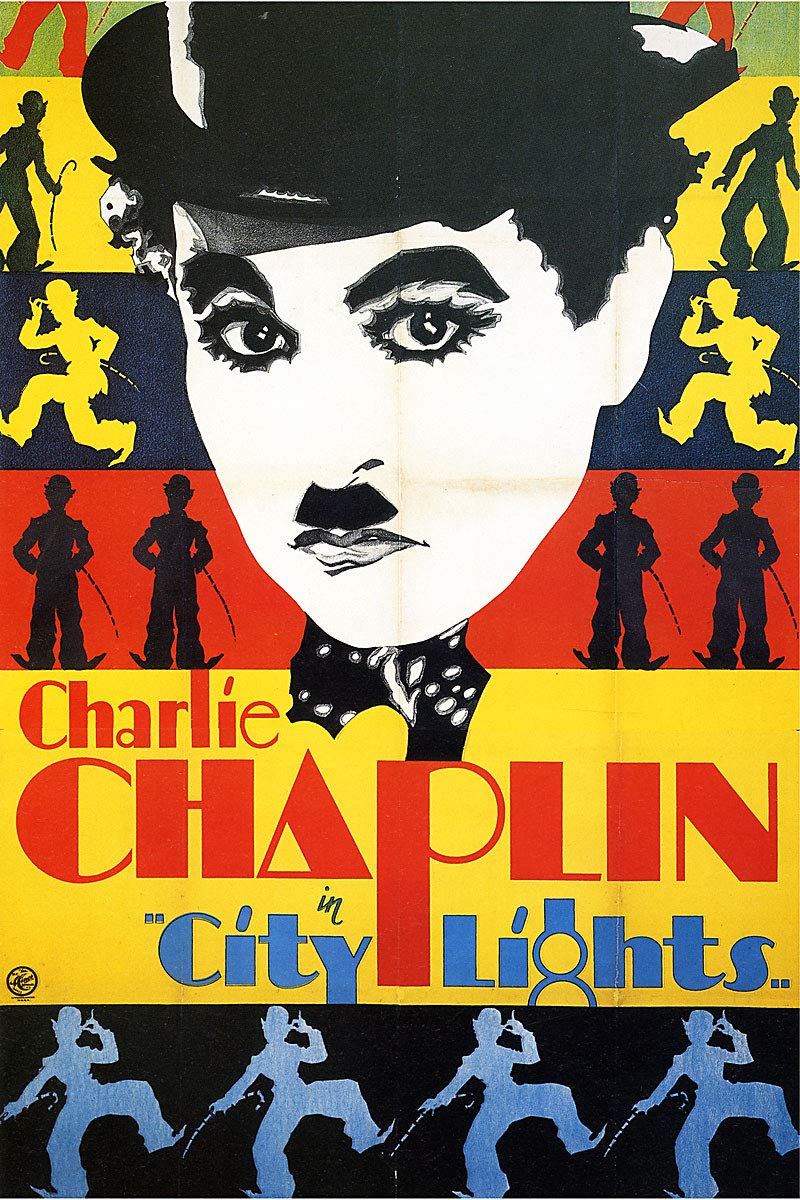

Starring and directed by icon and comic Charlie Chaplin, City Lights is cherished as one of the last hit silent films. However, what is sometimes missed on initial viewings of City Lights is how brilliantly it manages to meld comedy and critique to tell a poignant and entertaining story about modern America.

As French film critic Georges Sadoul writes in Dictionary of Filmmakers, “Throughout his career, much of Chaplin’s comedy grew out of how his ‘little man’ punctured the pomposity of the upper class.” While Chaplin’s sensibilities have always been grounded in the struggles of the working class (despite his massive financial success and many controversies), City Lights is a film in which those sensibilities shine. Defiantly silent during the early era of “talkies”, it is at the cornerstone of Chaplin’s critical success and legacy as a filmmaker. City Lights uses satire, symbolism, and metaphor folded into beautifully choreographed slapstick and heart touching moments to both entertain audiences and deliver critique on American society accessible to broad audiences.

The story in City Lights

City Lights at its core is about the relationship between a blind woman and Charlie Chaplin’s iconic character “the Tramp”. Influenced by commedia dell’arte, British tramp comedians, and his own life experience, then vaudeville performer Charlie Chaplin concocted his Tramp character, who would go on to be a protagonist in many of his films. In City Lights, through trickery of sound, an impoverished blind girl comes under assumption that the Tramp is a wealthy man. Charmed by her warmth and gentle kindness, the Tramp falls for her and doesn’t correct her assumption. After getting to know her, he learns she will soon be evicted and that she needs an expensive surgery to treat her blindness. The Tramp goes to great and comedic lengths to get money for her and preserve his image as a rich benefactor. After once again saving the life of his drunken millionaire friend during a robbery, the drunken millionaire gives the Tramp money as a gift. But after sobering up, the drunken millionaire suspects the Tramp of stealing the money and he is sent to prison.

Social criticism nestled in physical comedy

In the opening scene of City Lights, a large crowd gathers around the unveiling of a new statue in front of a government building. But when the tarp is pulled down for the reveal, the Tramp sleeps in the statue’s arms. After much shouting, the Tramp awakes and begins his not-so-elegant descent down the statue. This scene is not only well choreographed physical comedy, but also pokes fun at American society. It starts with the ironic name of the statue, “Peace & Prosperity”. Despite its name, the downtrodden and presumably homeless Tramp makes it his resting place. This juxtaposition of the grand, expensive statue with impoverishment creates visual dissonance – a celebration of wealth and status, while many suffer without basic necessities. The image of the Tramp sleeping on the statue provides a concise and powerful contrast of decadence against the material conditions of poverty.

The metaphor continues as the national anthem begins forcing all of the shouting crowd to stop. The Tramp, hoisted by his pants on the end of one of the statue’s fingers, also attempts to salute for the national anthem. Even as he is nearly injured by the statue, he still motions respect, even going as far to tip his hat to each figure of the statue, as he climbs down. Author and film historian Gerald Mast in The Comic Mind writes the opening scene, “… thumbs its nose at sanctimoniousness, civic pride, the glorification of dead forms and dead things at the expense of living people and living values.”

While the Tramp’s actions could be read as naive patriotism, it is much more likely a tongue and cheek, indicating the irony of blind patriotism for aging institutions at the expense of regular citizens. The police and officials remain unconcerned for the well-being of the Tramp, but instead the unveiling of the statue, serving as a metaphor for power working in protection of physical property and the symbolic power of wealth, before serving in protection of its citizens.

The critique in City Lights arguably is not only successful in spite of its comedic framing, but more so because of it. Made and released during the Great Depression, the working class themes are more accessible in comedy than they would be in a purely dramatic film. The comedic tone allows the critiques to be understood without being blatant or sappy. Chaplin’s refusal for the Tramp to be an object of pity, as might be the impulse in a solely dramatic film, maintains its accessibility. Yet, the film still trusts its audience to understand without getting heavy handed. With minimal dialogue and sound, the visuals work double time to jam pack both symbolic, practical, and comedic beats. Chaplin’s critique is made clear through concise visual language, making it unpretentious but not condescendingly simple.

Subtle heartbreak in the final scene

City Lights isn’t a one trick comedy pony, as it is able to tackle both the ridiculously slapstick and the intimately heartbreaking. There is no scene that better exemplifies this than the final one. The most powerful moments of metaphor in the final scene only come when the blind woman, not recognizing the Tramp, meets eyes with him. He recognizes her immediately and smiles widely, but he quickly moves away. She follows him out to the street and beckons him mirroring his generosity and sensitivity to her at their first meeting. She doesn’t recognize him until their hands touch, when she realizes her rich benefactor is in fact a poor man in no better conditions than she was in herself. The final lines delivered through title cards are “You can see now?” spoken by the Tramp and “Yes, I can see now. “ by the blind woman. Both literally and metaphorically the blind woman has gained sight, both in her new ability to see and her now metaphorical view of the truth. The final scene is very ambiguous and bittersweet. Mast writes that the final image of the Tramp’s face holds “… a look both joyful and anguished of happiness for her and awareness that the identity of her benefactor might cause her pain, of the joy of seeing her and the fear that she might now reject him after seeing him.”

City Lights knows when to be over the top and this scene isn’t. Charlie himself recognized that up until the end of his life, “…in City Lights just the last scene … I’m not acting …. Almost apologetic, standing outside myself and looking … It’s a beautiful scene, beautiful, and because it isn’t over-acted.” The scene gives no more than we need to understand the impact of the Tramp’s deceit on himself and the blind woman. Trapped by his circumstances and station in life, the Tramp’s actions read as self sacrifice against systemic odds. The subtlety and ambiguity of the scene leaves viewers in a limbo of satisfaction, allowing us to complete the story as we please.

Final thoughts

City Lights trusts audiences to understand the underlying meanings and connect with the story without overwrought details.. Modern day audiences might doubt a physical comedy to deliver on social critique and nuance, but much of Charlie Chaplin’s work does exactly that. Chaplin’s critical and commercial success is in part due to having a body of work that protaganizes the impoverished while levying criticism against the wealthy through symbolic language. Audiences laugh with the Tramp and root for him, all while booing the owning class villains. City Lights deserves its crown not only as a masterclass in physical comedy, but also as a powerful example of storytelling and social criticism.

Want to read more? Check out Ronny’s Review of Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel and read Jaxson’s thoughts on this years Game Developers Conference.